The contributions of Sudbury’s underground SNOLAB to the breadth of human knowledge have been many and varied.

Many Sudburians know just how important the lab, located a couple of kilometres below the surface in Creighton Mine, is to science, but now the world knows, too.

Last night, the annual Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded and a researcher at the Nickel City’s SNOLAB was one of the big winners.

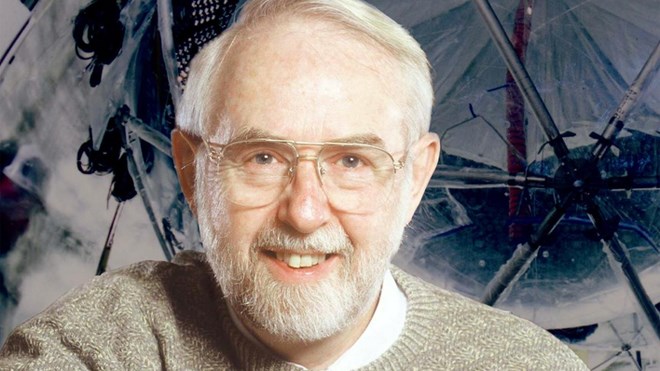

Dr. Arthur B. McDonald shares the 2015 award, the most prestigious award in science, with Dr. Takaaki Kajita a researcher from Japan.

Their discovery: Neutrinos, tiny particles once thought to be without mass, actually have some weight to them.

For most of us, this discovery means very little. But to scientists, it’s huge.

“The discovery has changed our understanding of the innermost workings of matter and can prove crucial to our view of the universe,” the Nobel committee said in announcing the award.

About 15 years ago, Kajita discovered neutrinos from the atmosphere switch between two identities on their way to the Super-Kamiokande detector in Japan.

Meanwhile, the research group in Canada led by Arthur B. McDonald at SNOLAB in Sudbury demonstrated that neutrinos from the Sun were not disappearing on their way to Earth. Instead, they were captured with a different identity when arriving at SNOLab.

The discoveries led to the conclusion neutrinos, which for a long time were considered massless, must have some mass, however small.

For particle physics, this was historic. For 20 years, the Standard Model of the universe and its inner-workings explained quite a bit about how reality works, but that model requires neutrinos to be massless.

McDonald’s and Kajita’s discoveries showed that the Standard Model cannot be the complete theory of the fundamental constituents of the universe.

Now the experiments continue and intense activity is underway worldwide in order to capture neutrinos and examine their properties. New discoveries about their deepest secrets are expected to change our current understanding of the history, structure and future fate of the universe.

McDonald is a professor emeritus at Queen's University in Kingston, where he holds the Gordon and Patricia Gray Chair in Particle Astrophysics. From 1970 to 1982, he worked as a research officer at the Chalk River Nuclear Laboratories northwest of Ottawa, before becoming a professor of physics at Princeton University from 1982 to 1989.

He shared the 2007 Benjamin Franklin Medal in Physics "for discovering that the three known types of elementary particles called neutrinos change into one another when traveling over sufficiently long distances, and that neutrinos have mass."

Join Sudbury.com+

- Messages

- Post a Listing

- Your Listings

- Your Profile

- Your Subscriptions

- Your Likes

- Your Business

- Support Local News

- Payment History

Sudbury.com+ members

Already a +member?

Not a +member?

Sign up for a Sudbury.com+ account for instant access to upcoming contests, local offers, auctions and so much more.